An Explorer’s Guide to Journaling Outside

This guide is meant to be used outside in natural spaces. There are a great deal of resources (books, apps, outdoor play.. ) and activities that can be interwoven and springboard from these tasks. This guide is meant to help with finding new ways of which to inspire world views that are awakened from the land. Holding a journal in one's hand evokes emotion and awe because we innately relate to the sensory details captured in words and images. Creating a journal has the bonus of allowing the person journaling to see and enjoy more deeply.

A journal is to think: to observe, to ask and answer questions, collect information, reflect, and understand. Also, to create a sense of personal responsibility with regard to protecting and cherishing our natural world through creative opportunities.

Painted in brushstrokes that call to the field, forest, riverbank and also to the heart, An Explorer’s Guide to Journaling Outside, celebrates a sense of wonder, bearing witness to nature’s power to develop an Explorer’s Mindset. Above all, it inspires protection and action on behalf of the natural world. There is something transformational about teaching and learning outside. These are opportunities to recognize land as a partner in a reciprocal relationship. Nature-rich spaces and authentic outdoor learning can happen right in our backyards, our schoolyards, and local community. Observation journals help kids understand more about the world around them and engage their sense of curiosity.

By providing them with an opportunity to stop and look, they begin to notice things that they have never seen before. You can even set up an “observation station” in your house or a local park - somewhere that you observe consistently and can watch changes over time!

Suggestions are made for student and educators working in journaling the process to inspire them to become keen observers of the wildness in their own backyards, and to foster in them a desire to protect the wild world. Remind yourself that this is a journal to observe, record, and fully appreciate. This is not an art exercise and no judgments are made on art skills. Using all our senses to enhance our observations, we leave our artist fears behind and enjoy exploring nature, with time to observe. This Guide is for celebrating the magic of journaling through nature and the magic of language to foster stewardship and action. It is for anyone with an interest in the natural world who wants to explore through journaling activities.

Materials and Safety:

You will need this explorer’s guide, a blank notebook or journal, a writing tool (a pencil is great) and maybe something hard to write on (like a clipboard or clipboard). When heading outside to journal some things to consider to bring could be: binoculars, hat, colour pencils, fine-liner black marker, water, extra supply kits (for students who forget), sharpener, first aid kit (and other safety considerations; such as parent contact information).

You will also need access to some form of nature, this could be a plant grown in a pot, a naturalization space, or wilderness. This Guide is for use with a connection to natural spaces and places. Take it outside! Take it on expeditions, on walks, out into the school grounds.

All outdoor activities need to have safety precautions for your organization and area followed. Remember to think of the safety of the wildlife as well and have conversations about leaving ‘no trace’ and respect of plants and wildlife.

Helpful Tips and Tricks to Journaling:

As an educator, have clear intensions when working with students on journals I personally don’t want them to become an art project only (unless that is my specific intension on that lesson). I also don't want them to become glorified worksheets/ colouring pages, but learning tools. Instead of giving students printed sheets to guide students, students are guided by thinking routines and tasks. Depending on the age, experience, and focus, the educator/ guide may choose to give more specific directions to layout as sometimes:

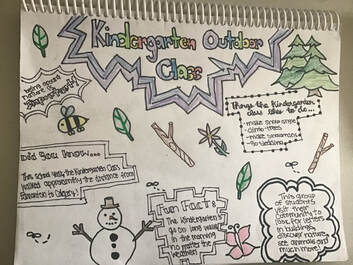

When working with younger students, printing out labels to add to the journal can be helpful. Labels that have a title and description of what you were working on that can be stuck onto a page (so when parents looked through they'd know what we were working on).

Sometimes working together is better. Journals can be created together as individual student’s drawings are added into one class journal.

These activities are not one-and-done but can be continually repeated to notice patterns over time or to explore new places together.

ASK

wander, look closely, observe, seek, query, question, exhort, request, invite, put forth, building curiosity

Many of the journaling tasks in the ASK Phase are meant to develop the mindset of questioning and wondering. Through journaling, the power of nature to amaze, bring joy, inspire wonder, and conjectures of the world around us helps students to develop questions to explore. Creating a journal to record ideas in response to the environment around you, helps create inspiration for engaging in questioning. As an educator/ guide, the following journaling tasks are for you to help guide students to their own ideas, questions, and interests. Through first deeply observing and reflecting and thinking about where things are how they are connected to other things and why that is important.

Activities:

Idle Doodling:

To still the busy mind and help focus on what is around us, an idle doodle can help clarify our thoughts and bring observations. This is a good introduction to observing without focus on a specific outcome. Letting go of the pressures of accomplishing a task or drawing.

What does it mean to be a part of nature?

What is your greatest responsibility to the land?

What does stewardship look like to you?

What does it feel like to be outside?

Local Inspirations:

What are local issues and questions interesting to you and connected to your community? Create a brainstorm page of ideas. Explore topics in your local community and make a web or brainstorm of interconnected ideas.

Going beyond: Add clippings of web links, images, and brief write ups that can help guide you and your students.

What do you notice around you that you think is important to notice?

What do you see around you that is connected to these issues?

What interesting news is happening?

Who can you connect with to help?

Special Places:

Student spend time in their own special spots. Encourage students to express what they have observed or felt at this spot by writing in their journal, drawing, or composing music.

Flow Writing and Drawing:

Write all your thoughts on a page as they come. Don’t stop writing. Even if it is, “I don’t know what to write and I need to keep writing until something comes to mind…” As you notice things around you, keep writing, describing, explaining, complaining, questioning, noticing… just keep writing.

Nature Poetry Inspiration:

Use a line of a nature poem as a kernel of inspiration. Write the line down in your journal. Take a book of your favourite poetry, open it to a page at random and rewrite a line that you connect with. Find a space outside to add your feelings, drawings and ideas. Keep going.

What connections can you make outside with that space and the lines of the poem?

What do you notice around you that relates to the feeling of the poem?

What can you add lines to the poem?

Noticing:

Find a space outside. Look around you and take in the what you see all around you. Make marks on your page. You do not have to look at your page, it is just to notice and make a mark on your page that represent things around you. A squiggle, a zigzag, an outline of a shape will do. Keep observing. Any marks will do.

When you look at your page, what to you notice about the lines (are they straight, ziggzaggy?) What can the lines and textures out outside tell you about that space?

Notice, Wonder, Think, See:

Finding a quiet space outside write down what you Notice around you. What sights, smells, sounds, …. Next, write what Wonders you think of in the process. What are you Thinking about in that space? What comes to mind that you may not notice, or wonder, but have a sense or understanding of. Finally, what do you See in that space? What specific evidence do you see. Remember to use descriptive language that will create an image for others.

Quest-everything:

This is a discussion made of only questions. The students write all the questions they can think of. Often one question will spark another question.

This works well as a group activity (as often questions inspire other questions). In a small group sit together outside in a circle. Only asking questions, but listening to each other’s questions and add questions on. As you work as a group, write down the questions you hear in your journal.

Who lived here in ancient times?

How was this land formed?

What creatures live here?

What makes it the place that it is?

Contour Drawings:

The key to this drawing exercise is to draw without looking at the paper. Place your pencil at the same point that your eye is looking at on the object’s surface. Contour drawings are a wonderful way to train your mind to slow down and truly examine an object. They will not often resemble the object you are drawing, but have made you observe closely. Do not lift your pencil from the paper and try not to look.

Wonder Words: Inspired from Lost Words by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris.

Add wonder words to a journal page: build up a treasure-chest of words for nature, weather, plants, animals, colour…

Beauty Hunt:

Beauty captivates nearly all of us. We may remark that a flower or a person is beautiful, but rarely articulate exactly what has captured our eye. Make six 2 x 2 in boxes on a journal page and go out seeking beauty. If a flower calls out to you, focus not on the entire flower, but on the aspect of the flower itself that defines its beauty. It may be the over-lapping peddles on the underside of the flower head, it may be the creation of the “negative space” defined by the winding stem of a vine, or the colours you see.

Beside each box, articulate the beauty in words.

Perspectives:

Try drawing something outside from different perspectives. Make 4 boxes on your page. You can divide your page down the middle and across (making 4 spaces). Try looking closely, then further away. Try looking from below, and above. Draw and write in each space what you see.

Drawing Something Upside - Down:

One mind-bending way of training the eye to look for detail is to actually draw upside down. Look closely at trees or pressed plant specimens. Turn the pictures upside down and observe the detail. Try to draw the upside- down specimen. When complete, turn the picture over to check for accuracy.

Suggestion, if it is hard trying to draw a whole tree upside down look along a pathway that had some pieces broken off on the ground. A smaller object on the page may be easier.

Follow Your Own Curiosity:

Going on a wonder-walk and observe. Afterward draw down the journey and discoveries you noticed along the way.

Dialogue:

If you could hear what the flowers, tress, rocks and everything around you would say, what do you think the conversation would sound like. Create a dialogue or conversations that you overhear... write this down in speech bubbles in your journal.

Word Associations:

Starting with one word in the middle, write the first word that comes to mind. Then, based on that word, add another. The next word only needs to connect to the one before it. Continue adding words and see where your mind wanders to….

Visible/Invisible:

When students are observing a system (such as a garden, a school, an ecosystem, etc.), there are almost always parts they can see, and parts that they can’t. Have students create a T-chart in their journal with one column for “visible” (parts you can see), and another for “invisible (parts you can’t see but can infer are there). For instance, if students are observing a plant, they can see the leaves and stem but they can't see the roots or the ground underneath.

From: California Academy of Science:

https://www.calacademy.org/educators/lesson-plans/introduction-to-scientific-sketching

Write Verbs:

Much of the energy of any sentence is carried in the verb. This task is inspired by the book, Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg where she provides an exercise to heighten our awareness of verbs and how we use them.

Write a list of 10 nouns of things you see around you. Using the space adjoining to your first list, make a list of 10 -15 verbs that describe the movement of those objects. Objects like rocks may be described as an action that happens upon them (such as throwing, or splashing into water, skipping, …).

Keep going, describe the place or thing in a paragraph using your list as inspiration.

COLLECT: gather, assemble, cumulate, call forth, meet, amass, embrace, summon, rally, come together, need-to-knows, research,

Some of the following journaling tasks can help guide students in collecting information in the field. The tasks you choose to do will center around your specific question or issue you are studying. The following explorations are to help gather data and solid background information. The goal is for the students to become experts on their topic (through outdoor journaling) to help support their continued learning journey.

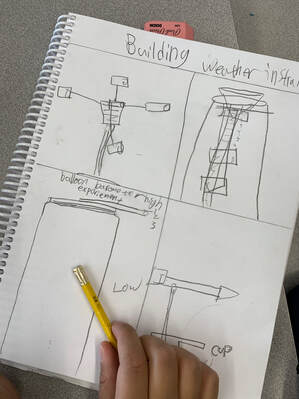

Notes, graphs, charts, and diagrams can all collect data in the journal. Graph and dot paper can be added into a journal to have more accurate information in mapping out where things are. There are many forms of scientific measurements that can be taken and added on one page, OR to each journal entry that is made throughout the time outside (for example the weather).

The journal is a place to collect things-- ideas, quotes, articles, images, lists, notes, etc. Collect those snippets of ideas and information that feed the thinking processes.

Sentence:

Create a sentence (or two) of statement that summarizes why your Inquiry is an important topic or issue. Go to an outdoor space and journal around it. Write and draw what you notice that adds ideas and throughs to these statements.

Descriptive Observation:

Choose an area with interesting plants, rocks and other natural features. Ask everyone to choose one natural item and to draw and write a description about what was observed, (without naming the exact item). When complete, students exchange journals to see if they can locate the item described.

Surveys:

Based on: https://www.oxbow.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Backyard-Nature-Survey_-Oxbow-Online-Resource.pdf

Students choose one square area to observe nature. They draw and write about what is found in that space.

Mapping Ideas:

For this activity it might be useful to start with an outline map showing the shape and dimensions of the area you will be looking at. This is usually available as a ‘base map’. Show students this base map and ask them how they would add to this map: What would they show? How would they measure distances?

As you explore, ask students to estimate distances along school walls, from window to ground, from end to end in the field, from one tree to another, etc.

Ask students how they will obtain and record data. Demonstrate how to hold tape measures to get distances, how to measure with a trundle wheel, and so on.

Here are three possibilities to journaling maps:

Do you feel the natural areas on their map are large enough?

Where would be the best place be if we were to create a naturalized area by planting trees, shrubs, or grasses?

What can a bird’s eye drawing show?

Green Mapping:

Going for a walk in your area, seek out the green in your community. Look for things like: green businesses, eco- friendly transportation, compost piles, recycling centre, organic gardens and natural areas in your community. Compile the information on a map in your journal. After compiling a master map of current community land uses, consider the community’s future. Consider things like: provisions for population increase; transportation systems; efficiency of energy use; balance of nature; balance of environmental, and social and economic health.

Memory Maps:

What memories do you have of these outdoor spaces? Map out and write in the details of these spaces and explain why they hold memories for you.

Interviews: Notetaking of Community Member Conversations:

NOTE: This activity often takes practice and guidance for youth to: be able to keep notes, know the appropriate behaviour and expectations, and think about meaningful questions to ask. I also work with the individual(s) before the meeting to send them some sample questions we will be asking (brainstormed as a group beforehand), length of time, and clarity on our expectations and goals of the task.

Meeting and having a conversation outside with a community member. There are so many people who are in our own communities that have a connection to place. Connecting with an indigenous elder, a local gardener, city planners, scientist, photographer … Create a journal page that represents what they have shared and what they have shown you in that outdoor space.

What is their relationship with the outdoor space?

What key information did they share?

Extension: after keeping notes the students can circle all the comments that:

Are important to your community.

Could help you answer a geo-inquiry question (a community question or issue).

What could we do to lead to positive change.

What could you learn by answering these questions or issues?

Temperature and Weather:

The temperature and weather can be collected through-out the year. An excellent example of this can be seen here: https://www.pyrosketchology.com/nature-journaling-before-fire

The weather can also be added in as a note on the side of journal page every time students sketch outside to have a running document.

Water:

Water can be tested for the pH, temperature, clarity, among other things. A daily journal of these facts can be added into squares for each day.

Sound Map

Close your eyes and listen. Rarely are we in a completely silent space.

Tell students about deer ears, which are shaped to pick up the slightest noise from the surrounding area. Have students cup their hands so that if you were to pour water into their hands they would be able to hold some - and then have them put their cupped hands behind their ears to listen to naturally occurring noises.

In a bottom corner they draw the map’s key. Each new sound heard will be represented with a symbol they come up with and recorded in the key. Ask students to also draw an X and their name on the place they are on the map. As each new sound is heard, the symbol is recorded on the map at where it was heard relative to the X on the map.

Now focus on one sound and translate that sound into an image. Draw that sound, listen for a new sound, draw again. The very act of translating a sound into an image, forces students to pay attention and describes a part of the environment.

How did you feel about the human sounds you heard? Why?

Are their sounds you cannot identify?

Patterns:

Patterns can be seen everywhere in nature. There are large patterns (such as the year), as well as small patterns (such as branches).

Sun Dial:

On a sunny day, give each pair of students a pointed stick. Ask the students to find a spot in the grass where they can push the pointed stick into the ground, so it stands upright. Tell them to mark where the shadow falls. Have the students return twenty minutes later, marking the tip of the shadow. Tell them to use the meter stick to form a line on the ground connecting the two marks.

Why does this line represent an east-west direction?

Ask the students how to determine the north-south line. (The north-south line will be perpendicular to the east-west line.)

Then ask the groups to draw a second line, crossing the first at a right angle. Verify their findings with a compass. Ask the students how they would use this activity if they were ever

lost.

How does the length of the object’s shadow change over the course of the day? Why?

After creating sundials, the students were able to make a sundial in their journals.

Food Webs and Food Chains:

Taking what students know about food webs and food chains, go outside and add in what they can find that represents key aspects.

What producers, consumer, or decomposers are evident in your area?

What food chains and food webs do you want to learn more about?

Scale- perceptions:

Smaller scales can inform our understanding of that object. Map-makers use defined scales—usually a large-scale map depicts a small geographic area in great detail while a small-scale map depicts a large geographic area in much less detail. Find one object that interests you. Draw it in the middle of a journal page at the scale that feels the most manageable. Now above and below your first sketch, use a larger scale and a smaller scale to view the same object.

How does this affect your perception of the object?

What does observing something from a new perspective make you learn more about it?

Close-Up Observations:

Students love getting a "window" to draw and focus on one spot. Cut a picture frame out of cardboard or thick paper. Place this on the ground (or have students look through) to focus on one small area. Have them focus on things they may not have noticed before.

What small things to you notice? Make sure to label the size (either estimation based on referent like the size of my thumb nail, or using a small ruler).

How small is it when it is born?

How far does it travel?

Tree Observations:

There are a variety of observations and data collect that can be made with trees. Choose a tree for the exploration. You may want to bring out some tree identification keys so the students can identify their tree. Students could record the following observations for each visit: date; estimate of the number of leaves or needles (this can be done by counting the leaves or needles on the lower branches, then count the number of branches, and multiply); the colour of the leaves; obvious changes since last visit. After collecting the base data for each visit, any series of activities can be drawn together around the specific tree. For instance, students might observe, sketch, identify and research…

Here are some ideas:

Ask the students to work together to write a paragraph about their tree. Their description should be so specific that a stranger could locate their exact tree with just this information.

Have them move around their tree to get different views.

Draw the general silhouette shape of the tree.

Look from the bottom of the trunk up to the top of the branches and draw what you see.

Locate any roots that might be visible at the tree’s base.

Do a tree bark rubbing (by hold a loose sheet of paper on the trunk and lightly rubbing a crayon or chalk along the sheet). How does the bark compare to the skin on their own hands? Is the bark rougher or smoother; warmer or colder; wetter or drier; darker or lighter than your skin?

Tell the students to look for and sketch any seeds, cones or flowers.

Listen to the sounds made by the tree. How can you draw the sounds in your journal?

Ask the students to look for small holes in the tree, or other places where animals, or other plants might be living.

What animals live in or use this tree?

What do you see on the tree?

Why does a tree need roots? (food and water transport, support).

If the tree is coniferous, ask the students to search for some sap or resin and describe its texture and scent. Tell them to rub a bit of the resin next to the bark rubbing in their journal. Why do you think the resin is sticky?

Draw the branching pattern of the tree.

How do the branches come out of the main trunk?

Have the students describe the colour and shape of the leaves or needles.

Sketch or trace a leaf. Describe the edge of the leaf.

Why does a tree need leaves? (Leaves photosynthesize, or produce food, with the help of sunlight, air and water.)

How do the leaves or needles come off the branch? Are they in opposite pairs; or alternating around the branch; or do they come off in a whorl, like a shirt collar?

Collect and sort leaf samples to determine the plants growing in the natural area. Classify leaf shapes and draw the details.

Insect Observations: Remember to talk about the importance of how to release and unharmed insects.

Idea from: https://resources4rethinking.ca/media/5%20Min-Fieldtrips.pdf 5 Minute Field Trips by GEOEC

Lay a white sheet below a small bush or shrub and have students rustle the bush so that anything clinging to the branches or leaves will fall out. Show how items like magnifying glasses can be used, and briefly model the observation skills you would like students to use.

Other idea for observing insects include:

Search for and investigate the creatures living in the mulch layer of the soil.

Search for and investigate galls on plants to see who lives where.

Investigate an insect’s behaviour by making observations of a single insect’s journey. Draw the insect looking closely or draw the line of where the ant moves (creating a squiggle across your page).

Plant Watch:

Sketching and journaling is a wonderful way to get to know the plants around you. As students focus on the details they will often see many details and find a deeper sense of that plant. Again, this is not an art task to draw the perfect flower, but rather a way for student to develop deep observation skills and notice. Students develop scientific skills while observing changes in plants and learning about biodiversity.

There are many observations that can be made while looking at plants. Some include:

How many petals?

Draw what the fragrance of the flowers would look like. What colour would it be?

Are the leaves alternating, or opposite on the stem?

Draw the plants life cycle.

Show its seed.

Students monitor the flowering and document the bloom times.

If the plant faces threats, such as pollution or loss of habitat, students can develop a recovery plan.

Observe and identify native flowers.

Monitor pollinator populations in natural area.

The sky’s the limit for ideas on how one student and one plant can relate.

Ethnobotany is the study of how plants have been used by various people and cultures around the world. Seek local examples of plants that were traditionally used for food, beverages, and medicinal remedies.

Tracks and Scat:

A great way to have students engage in the winter months is to draw the tracks that are found around them. Remember to show how the tracks are placed (as often it shows the type of movement of the animal).

Feeling:

Colours and memories can often add to the feeling of a space. Instead of trying to draw what you observe, try drawing capturing the feeling of a space.

What colours are there?

What textures can capture the mood?

Tracing:

Students love tracing. A leaf, rock or other treasures found on the ground can be observed with details in the tracing.

Six Directions:

Developed from Lynda Barry's book What It is: Do You Wish You Could Write?

Sit is space and notice what is up, down or below, in front, behind you and on both sides. Make 6 boxes on your page and document what you notice.

The Natural Cycle: Adapted from Coyote’s Guide

Prepare a series of cards (8.5 x 11 cardstock) with each of the 8 cardinal directions on it, and another set of cards for each layer of meaning that you want to introduce:

■ Directions

■ Times of day

■ Seasons

■ Stages of Life

■ Qualities of the 8 directions / energy levels

■ Learning cycle

Get students sitting in a circle and ask them to point in the 8 cardinal directions. Ask them what comes to mind when they think of each of those directions.

Place the cards for the 8 directions in front of students in the correct orientation.

Introduce as many new layers of meaning as you would like, for example “Here are the different stages of life (Infant, Toddler, Child, Adolescent, Young Adult, Adult, Elder...) and where would they fit in the circle?.” Discuss. This can be connected to Indigenous teachings through the integration of the Medicine Wheel teachings. The complexity of meaning for each direction will be differentiated depending on your group.

Six Room Poetry:

from Georgia Heard's book Awakening the Heart: Exploring Poetry in Elementary and Middle School.

VISUALIZE

envision, picture, see, imagine, evoke, fancy, dream up, conceptualize, think about, forecast, anticipate,

In this stage the students are creating compelling visuals and organizing data to deeper understand, and analyse data that was collected. It is a visual representation of data and information. In this phase, students show how they are fully immersed in a sense of their surroundings and have a deep connection and understanding. Nature journaling exercises often find different ways of seeing, thinking and organizing information, and this helps with the storytelling of this journey. The students may have started visualizing their information already as they engaged in the collect phase. The following are ideas on how to continue to organize and present that information.

Boxes:

Info-doodles:

Create a page of integration of words, images, numbers, and shapes for the purposes of learning and sharing what has been learned. Students use both words and sketches to communicate their ideas. Encourage them to include labels, arrows, diagrams, and anything else to make their thinking clear to another scientist.

Word Cloud:

Create a word cloud by making a collection, or cluster, of words depicted in different sizes (and you can play with different fonts).The bigger and bolder the word appears, the more important it is.

Concept- Map:

A concept map begins with a main idea, typically placed in a circle, and then has lines connecting the main idea to other ideas. This strategy helps students visualize relationships among different concepts. Reviewing their concept maps will give you a sense of students' understanding, how their ideas are connected, and any gaps or misconceptions they may have.

Frayer Model:

From: A Schema for Testing the Level of Concept Mastery by D. A. Frayer, W. C. Frederick, & H. G. Klausmeier.

The term being looked at is added into the middle of the page. Around the outside there are definition, characteristics, example, and non-examples.

Descriptive Observation:

Look through your journal and think about what observations you have made. Create a page in the journal that summarizes the story or journey you have been on.

What are some key things you think that can be helpful in a story page?

What other observations can you notice?

What data can you observe in this space, that can help you at the end of the geo-inquiry process to compare how you have impacted this space for the better?

Create a time line of your natural area:

When you step outside your door each day to interact in the natural world, consider who may have walked this land before you and who will walk this land after you are gone?

Think about how the land supports your health and well-being, and that of your family, community and all non-human entities within the web of life?

Think-Pair-Share with Writing:

Students write their own thoughts in the first box during the "think" period. After the "pair-share" discussion with a partner (or partners), they write down what their partner said in the second box. Finally, they record in the third box how the conversation has changed or confirmed their initial ideas.

Information Cards:

Information cards are cards that can be kept in a pocket made in the journal to remember key information and facts. One side has the image to help you remember, and the other side has some information.

4 (see), 3 (feel), 2 (hear), 1 (smell):

4-3-2-1 -- The world is out there, ready to explore. Try “4, 3, 2, 1” as a way to tune into your observations; taking time to engage your sense in the natural world. Outside find 4 things you can see, 3 things you can feel, 2 things you can hear, and 1 thing you can smell.

What do you notice?

This task can also be adding information and ideas for what we have shared in the journal earlier about a space.

CREATE: design, originate, invent, initiate, devise, frame, shape, form, forge, establish, bring about, foster, sow the seeds of, inspire, enkindle

At this phase the journal becomes a way to convey a story that has formed from the data and information. It represents how to show the answers you have found about your geo-inquiry.

Thinking routines can be used in journaling to help build guidance related to helping students construct explanations. Thinking routines include: sentence frames, graphic organizers, and guiding areas to show.

I think...because...

This simple frame helps students start to develop explanations. The words “I think” allows students to share their ideas while leaving room for differing opinions. The word “because” reminds students to support their claim with evidence and reasoning.

At first, I thought...

This frame allows students to reflect on their initial predictions and consider whether new evidence has either confirmed or challenged those ideas. The structure of this frame embodies the work of real scientists; scientists are constantly analyzing evidence from new studies to determine whether or not it upholds their previous ideas.

Phenology Wheel:

The word Phenology (according to the Merriam Webster dictionary) means the study of cyclic and seasonal natural phenomena, especially in relation to climate and plant and animal life. You can use a phenology wheel to keep track of anything really.

(some examples: http://partnersinplace.com/gallery/ )

Reflections:

Take photos of an experience, or of the students in the environment, and glue those into the journal. They can then write around it and describe the feeling, setting, experience... They can also draw diagrams of things they noticed in that experience around it.

Schoolyard Eco-calendar:

What and when do things happen in your area? After a year of collecting data, you can custom design a calendar to highlight the natural events you’ve experienced. Your calendar could include: average temperature; bloom dates of flowers such as dandelions; moon phases; date of returning birds and insects.

Mood Board or Inspiration Page:

A mood board is an arrangement of images, materials, pieces of text. The collage is meant to evoke or project the essence of the land around you through art and words. This is a collection of what is noticed and observed in one area. You can add colour squares of the colours you see in this space, photos or drawings, textures, patterns, text, anything visually inspiring.

Storyboards:

A storyboard is a way to visualize the story the students would like to share about their geo-inquiry. At their core, storyboards are a set of sequential drawings to tell a story. Creating a linear direction of boxes that can show the passage of time, or the steps in a process.

Observations – Reflections:

Creating a T-chart in the students journals they can make a list of observations that have made and personal reflections based on those observations.

ACT: making heart connections, take the initiative, react, proceed, gesture, conservation, show, influence, change, transform, take part, deed, empowered,

Through journaling the students develop a personal connection with nature. At year’s end, you’ll have a keepsake of your favorite adventures and places, and a step into action. The action could be a piece that has risen from the journal or the sharing of the journal itself. The action will be rooted in the inquiry the students started with. When choosing how and where to take-action, the audience will need to be considered. It is important to select an authentic audience. This will allow the students to engage in a meaningful way. By having an authentic audience, the students are able to share their inquiry story with others to create a positive action. The audience could be local community members, government officials, scientists…

Art Display in Community to Share Information with Others:

Students created artwork based on their journal observations to share with community members.

Nature Cards:

A way students can share information and encourage action within their community could be through making cards (with information that could be mailed to the government, local leaders, community members, etc.). They can base them on the information the students have found and be shared out into the community as gift cards, letters, or trading cards.

Scientific Sharing:

There are more and more citizen science programs that allow students to contribute to real-life data sharing. They learn about ecological relationships while contributing to a monitoring program. Scientists benefit from the trends and information the students contribute to. This valuable information can help in a variety of ways, including wildlife management (e.g..., in early springs more deer fawns are successful), human health (pollen warnings for allergy sufferers) and tourism (best times to photograph or observe particular flowers, animals, etc.) Information the students collected in their nature journal could help contribute to a citizen science project in your local area.

Gallery Walk:

A great way for students to share their journal work is to set up a gallery walk. Students invite the local community to take a walk through the outdoor space where students have displayed their journals. Information can be shared during this time with the community members about what the students were observing through students showing their journals.

Posters of information:

Using the journal work the students have developed, the students could create a final poster to share with others. This poster would show information and images about the scientific studies and observations they have made.

References:

You can take the National Geographic Geo-Inquiry Course (and many other amazing courses) here: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/education/professional-development/courses/

Acknowledgements:

Many of the activities in The Explorer’s Guide to Journaling, are the “classics” of nature journaling. Teachers are the magpies of ideas and treasured activities get collected. We collect something we saw someone teach, or snippets of what we have read and make it our own lesson. In an attempt to unravel the pieces these ideas developed from, I have tried to show references. If you come across something that you know the original reference, please let me know: [email protected]

The author gratefully acknowledges the following authors for their invaluable contributions to art journaling and environmental education. Their works are still favourite books, website, and resources:

John Muir Laws, website and resources are a gift to anyone interested in learning more about nature stewardship through art journaling. A number of the activities in this guide have been gathered from seeds of ideas in his work from his book and website including: How to Teach Nature Journaling: Curiosity, Wonder, Attention by John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren.

Claire Walker Leslie has informative and helpful books and workshops about art nature journaling. She is at the forefront of the nature observation and journaling movement. She has many helpful books including: KEEPING A NATURE JOURNAL: Deepen Your Connection with the Nature Around You.

Joseph Cornell, is a brilliant nature educator. He has produced, among other things, two classic outdoor activity books, Sharing Nature With Children, and Sharing the Joy of Nature. These two books are a complete library of outdoor experience and learning activities.

David Sobel’s books, are wonderful reads. In Place-Based Education: Connecting Classrooms and Communities, he shares many ideas for getting students connected to the outdoors. He eloquently states what many of us already intuitively know, “If we want children to flourish, to become truly empowered, then let us allow them to love the earth, before we ask them to save it.” This Guide is designed to do just that.

There is a program that was started at the University of Calgary that focuses on sketch journaling. Campus Calgary - Open Minds . I was fortunate to be selected to attend a few times (City Hall School, Bird School, and Community Arts Commons). We get to go to that space for a full week to learn by talking to experts, interacting with the space, and sketch journaling. I learned a great deal about journaling through this program.

There are also some amazing ideas from Harvard through Project Zero and Visible Thinking Routines, that show how to use thinking routines to note take

BOOKS:

HOW TO TEACH NATURE JOURNALING CURIOSITY . WONDER . ATTENTION by John Muir Laws and Emilie Lygren

See a link here:

https://johnmuirlaws.com/product/how-to-teach-nature-journaling/?attribute_format=Free+PDF+double-page+%28screen+viewing%29

Keeping a Nature Journal: Deepen Your Connection with the Natural World Around You by Clare Walker Leslie

https://www.storey.com/books/keeping-a-nature-journal-3rd-edition/

The Curious Nature Guide: Explore the Natural Wonders All Around You by Clare Walker Leslie

Keeping a Nature Journal: Discover a Whole New Way of Seeing the World Around You by Clare Walker Leslie, and Charles E.Handbook of Nature Study by Anna Botsford ComstockSee the link here: https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9780801493843/handbook-of-nature-study/#bookTabs=1

Ideas for Supporting Students:

https://vimeo.com/38247060

Suggested Facebook Groups:

The Nature Journal Club

Suggested Instagram Links:

@raisinglittleshoots

@give.them.beauty

@flouris.with.charlotte

@ourquietgrowingtime

Websites:

Open minds:

https://cbe.ab.ca/ccom/Pages/Home.aspx

John Muir Laws:

https://johnmuirlaws.com/

Including free video’s for journaling: https://johnmuirlaws.com/blog-archives/

Observing Nature:

http://www.natureworkspress.com/ObservingNatureJournalSketchingGuide.html

Beyond Land Acknowledgement:

https://etfofnmi.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Going-Beyond-A-Land-Acknowledgement-FINAL-VERSION.pdf

Science Notebook Corner:

https://www.calacademy.org/educators/science-notebook-corner

Explorer’s Guide to Lost Words:

https://www.evajohn.co.uk/the-lost-words.php?declinecookies=1

California Academy of Science:

https://www.calacademy.org/educators/lesson-plans/introduction-to-scientific-sketching

Project Zero has a collection of examples of thinking routines: (http://www.pz.harvard.edu/thinking-routines#WithArtOrObjects)

The Frayer Model comes from A Schema for Testing the Level of Concept Mastery by D. A. Frayer, W. C. Frederick, & H. G. Klausmeier, Technical Report No. 16. Copyright 1969 by the University of Wisconsin.

Examples and Inspiration from People Who Journal:

https://www.scratchmadejournal.com/

https://www.exploringoverland.com/fieldarts

https://robinleecarlson.com/

http://marleypeifer.com/nature-journaling-education/

https://lauriewigham.com/paintings

https://www.lesleygoren.com/client-projects

https://www.exploringoverland.com/constantapprentice/tag/nature+journaling

https://pyrolife.lessonsonfire.eu/category/fire-science-for-all/

http://www.clarewalkerleslie.com/books.htm

https://www.learningbyinquiry.com/how-to-use-nature-journaling-in-inquiry-learning/

http://www.clarewalkerleslie.com/index.htm

This guide is meant to be used outside in natural spaces. There are a great deal of resources (books, apps, outdoor play.. ) and activities that can be interwoven and springboard from these tasks. This guide is meant to help with finding new ways of which to inspire world views that are awakened from the land. Holding a journal in one's hand evokes emotion and awe because we innately relate to the sensory details captured in words and images. Creating a journal has the bonus of allowing the person journaling to see and enjoy more deeply.

A journal is to think: to observe, to ask and answer questions, collect information, reflect, and understand. Also, to create a sense of personal responsibility with regard to protecting and cherishing our natural world through creative opportunities.

Painted in brushstrokes that call to the field, forest, riverbank and also to the heart, An Explorer’s Guide to Journaling Outside, celebrates a sense of wonder, bearing witness to nature’s power to develop an Explorer’s Mindset. Above all, it inspires protection and action on behalf of the natural world. There is something transformational about teaching and learning outside. These are opportunities to recognize land as a partner in a reciprocal relationship. Nature-rich spaces and authentic outdoor learning can happen right in our backyards, our schoolyards, and local community. Observation journals help kids understand more about the world around them and engage their sense of curiosity.

By providing them with an opportunity to stop and look, they begin to notice things that they have never seen before. You can even set up an “observation station” in your house or a local park - somewhere that you observe consistently and can watch changes over time!

Suggestions are made for student and educators working in journaling the process to inspire them to become keen observers of the wildness in their own backyards, and to foster in them a desire to protect the wild world. Remind yourself that this is a journal to observe, record, and fully appreciate. This is not an art exercise and no judgments are made on art skills. Using all our senses to enhance our observations, we leave our artist fears behind and enjoy exploring nature, with time to observe. This Guide is for celebrating the magic of journaling through nature and the magic of language to foster stewardship and action. It is for anyone with an interest in the natural world who wants to explore through journaling activities.

Materials and Safety:

You will need this explorer’s guide, a blank notebook or journal, a writing tool (a pencil is great) and maybe something hard to write on (like a clipboard or clipboard). When heading outside to journal some things to consider to bring could be: binoculars, hat, colour pencils, fine-liner black marker, water, extra supply kits (for students who forget), sharpener, first aid kit (and other safety considerations; such as parent contact information).

You will also need access to some form of nature, this could be a plant grown in a pot, a naturalization space, or wilderness. This Guide is for use with a connection to natural spaces and places. Take it outside! Take it on expeditions, on walks, out into the school grounds.

All outdoor activities need to have safety precautions for your organization and area followed. Remember to think of the safety of the wildlife as well and have conversations about leaving ‘no trace’ and respect of plants and wildlife.

Helpful Tips and Tricks to Journaling:

As an educator, have clear intensions when working with students on journals I personally don’t want them to become an art project only (unless that is my specific intension on that lesson). I also don't want them to become glorified worksheets/ colouring pages, but learning tools. Instead of giving students printed sheets to guide students, students are guided by thinking routines and tasks. Depending on the age, experience, and focus, the educator/ guide may choose to give more specific directions to layout as sometimes:

- the journal is to document information.

- the students are asked to add information and research to their journal.

- it is so I can understand their thinking better and we can do an analysis in more depth.

- it is more so they can remember their thoughts and ideas.

- Truly, journaling is about communicating.

When working with younger students, printing out labels to add to the journal can be helpful. Labels that have a title and description of what you were working on that can be stuck onto a page (so when parents looked through they'd know what we were working on).

Sometimes working together is better. Journals can be created together as individual student’s drawings are added into one class journal.

These activities are not one-and-done but can be continually repeated to notice patterns over time or to explore new places together.

ASK

wander, look closely, observe, seek, query, question, exhort, request, invite, put forth, building curiosity

Many of the journaling tasks in the ASK Phase are meant to develop the mindset of questioning and wondering. Through journaling, the power of nature to amaze, bring joy, inspire wonder, and conjectures of the world around us helps students to develop questions to explore. Creating a journal to record ideas in response to the environment around you, helps create inspiration for engaging in questioning. As an educator/ guide, the following journaling tasks are for you to help guide students to their own ideas, questions, and interests. Through first deeply observing and reflecting and thinking about where things are how they are connected to other things and why that is important.

Activities:

Idle Doodling:

To still the busy mind and help focus on what is around us, an idle doodle can help clarify our thoughts and bring observations. This is a good introduction to observing without focus on a specific outcome. Letting go of the pressures of accomplishing a task or drawing.

What does it mean to be a part of nature?

What is your greatest responsibility to the land?

What does stewardship look like to you?

What does it feel like to be outside?

Local Inspirations:

What are local issues and questions interesting to you and connected to your community? Create a brainstorm page of ideas. Explore topics in your local community and make a web or brainstorm of interconnected ideas.

Going beyond: Add clippings of web links, images, and brief write ups that can help guide you and your students.

What do you notice around you that you think is important to notice?

What do you see around you that is connected to these issues?

What interesting news is happening?

Who can you connect with to help?

Special Places:

Student spend time in their own special spots. Encourage students to express what they have observed or felt at this spot by writing in their journal, drawing, or composing music.

Flow Writing and Drawing:

Write all your thoughts on a page as they come. Don’t stop writing. Even if it is, “I don’t know what to write and I need to keep writing until something comes to mind…” As you notice things around you, keep writing, describing, explaining, complaining, questioning, noticing… just keep writing.

Nature Poetry Inspiration:

Use a line of a nature poem as a kernel of inspiration. Write the line down in your journal. Take a book of your favourite poetry, open it to a page at random and rewrite a line that you connect with. Find a space outside to add your feelings, drawings and ideas. Keep going.

What connections can you make outside with that space and the lines of the poem?

What do you notice around you that relates to the feeling of the poem?

What can you add lines to the poem?

Noticing:

Find a space outside. Look around you and take in the what you see all around you. Make marks on your page. You do not have to look at your page, it is just to notice and make a mark on your page that represent things around you. A squiggle, a zigzag, an outline of a shape will do. Keep observing. Any marks will do.

When you look at your page, what to you notice about the lines (are they straight, ziggzaggy?) What can the lines and textures out outside tell you about that space?

Notice, Wonder, Think, See:

Finding a quiet space outside write down what you Notice around you. What sights, smells, sounds, …. Next, write what Wonders you think of in the process. What are you Thinking about in that space? What comes to mind that you may not notice, or wonder, but have a sense or understanding of. Finally, what do you See in that space? What specific evidence do you see. Remember to use descriptive language that will create an image for others.

Quest-everything:

This is a discussion made of only questions. The students write all the questions they can think of. Often one question will spark another question.

This works well as a group activity (as often questions inspire other questions). In a small group sit together outside in a circle. Only asking questions, but listening to each other’s questions and add questions on. As you work as a group, write down the questions you hear in your journal.

Who lived here in ancient times?

How was this land formed?

What creatures live here?

What makes it the place that it is?

Contour Drawings:

The key to this drawing exercise is to draw without looking at the paper. Place your pencil at the same point that your eye is looking at on the object’s surface. Contour drawings are a wonderful way to train your mind to slow down and truly examine an object. They will not often resemble the object you are drawing, but have made you observe closely. Do not lift your pencil from the paper and try not to look.

Wonder Words: Inspired from Lost Words by Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris.

Add wonder words to a journal page: build up a treasure-chest of words for nature, weather, plants, animals, colour…

Beauty Hunt:

Beauty captivates nearly all of us. We may remark that a flower or a person is beautiful, but rarely articulate exactly what has captured our eye. Make six 2 x 2 in boxes on a journal page and go out seeking beauty. If a flower calls out to you, focus not on the entire flower, but on the aspect of the flower itself that defines its beauty. It may be the over-lapping peddles on the underside of the flower head, it may be the creation of the “negative space” defined by the winding stem of a vine, or the colours you see.

Beside each box, articulate the beauty in words.

Perspectives:

Try drawing something outside from different perspectives. Make 4 boxes on your page. You can divide your page down the middle and across (making 4 spaces). Try looking closely, then further away. Try looking from below, and above. Draw and write in each space what you see.

Drawing Something Upside - Down:

One mind-bending way of training the eye to look for detail is to actually draw upside down. Look closely at trees or pressed plant specimens. Turn the pictures upside down and observe the detail. Try to draw the upside- down specimen. When complete, turn the picture over to check for accuracy.

Suggestion, if it is hard trying to draw a whole tree upside down look along a pathway that had some pieces broken off on the ground. A smaller object on the page may be easier.

Follow Your Own Curiosity:

Going on a wonder-walk and observe. Afterward draw down the journey and discoveries you noticed along the way.

Dialogue:

If you could hear what the flowers, tress, rocks and everything around you would say, what do you think the conversation would sound like. Create a dialogue or conversations that you overhear... write this down in speech bubbles in your journal.

Word Associations:

Starting with one word in the middle, write the first word that comes to mind. Then, based on that word, add another. The next word only needs to connect to the one before it. Continue adding words and see where your mind wanders to….

Visible/Invisible:

When students are observing a system (such as a garden, a school, an ecosystem, etc.), there are almost always parts they can see, and parts that they can’t. Have students create a T-chart in their journal with one column for “visible” (parts you can see), and another for “invisible (parts you can’t see but can infer are there). For instance, if students are observing a plant, they can see the leaves and stem but they can't see the roots or the ground underneath.

From: California Academy of Science:

https://www.calacademy.org/educators/lesson-plans/introduction-to-scientific-sketching

Write Verbs:

Much of the energy of any sentence is carried in the verb. This task is inspired by the book, Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg where she provides an exercise to heighten our awareness of verbs and how we use them.

Write a list of 10 nouns of things you see around you. Using the space adjoining to your first list, make a list of 10 -15 verbs that describe the movement of those objects. Objects like rocks may be described as an action that happens upon them (such as throwing, or splashing into water, skipping, …).

Keep going, describe the place or thing in a paragraph using your list as inspiration.

COLLECT: gather, assemble, cumulate, call forth, meet, amass, embrace, summon, rally, come together, need-to-knows, research,

Some of the following journaling tasks can help guide students in collecting information in the field. The tasks you choose to do will center around your specific question or issue you are studying. The following explorations are to help gather data and solid background information. The goal is for the students to become experts on their topic (through outdoor journaling) to help support their continued learning journey.

Notes, graphs, charts, and diagrams can all collect data in the journal. Graph and dot paper can be added into a journal to have more accurate information in mapping out where things are. There are many forms of scientific measurements that can be taken and added on one page, OR to each journal entry that is made throughout the time outside (for example the weather).

The journal is a place to collect things-- ideas, quotes, articles, images, lists, notes, etc. Collect those snippets of ideas and information that feed the thinking processes.

Sentence:

Create a sentence (or two) of statement that summarizes why your Inquiry is an important topic or issue. Go to an outdoor space and journal around it. Write and draw what you notice that adds ideas and throughs to these statements.

Descriptive Observation:

Choose an area with interesting plants, rocks and other natural features. Ask everyone to choose one natural item and to draw and write a description about what was observed, (without naming the exact item). When complete, students exchange journals to see if they can locate the item described.

Surveys:

Based on: https://www.oxbow.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Backyard-Nature-Survey_-Oxbow-Online-Resource.pdf

Students choose one square area to observe nature. They draw and write about what is found in that space.

Mapping Ideas:

For this activity it might be useful to start with an outline map showing the shape and dimensions of the area you will be looking at. This is usually available as a ‘base map’. Show students this base map and ask them how they would add to this map: What would they show? How would they measure distances?

As you explore, ask students to estimate distances along school walls, from window to ground, from end to end in the field, from one tree to another, etc.

Ask students how they will obtain and record data. Demonstrate how to hold tape measures to get distances, how to measure with a trundle wheel, and so on.

Here are three possibilities to journaling maps:

- Areas that are useful for plants or animals.

- The different types of play that occurs.

- Noisy areas and quiet areas.

- Evaluate the habitat potential of the residential yards that border the school.

Do you feel the natural areas on their map are large enough?

Where would be the best place be if we were to create a naturalized area by planting trees, shrubs, or grasses?

What can a bird’s eye drawing show?

Green Mapping:

Going for a walk in your area, seek out the green in your community. Look for things like: green businesses, eco- friendly transportation, compost piles, recycling centre, organic gardens and natural areas in your community. Compile the information on a map in your journal. After compiling a master map of current community land uses, consider the community’s future. Consider things like: provisions for population increase; transportation systems; efficiency of energy use; balance of nature; balance of environmental, and social and economic health.

Memory Maps:

What memories do you have of these outdoor spaces? Map out and write in the details of these spaces and explain why they hold memories for you.

Interviews: Notetaking of Community Member Conversations:

NOTE: This activity often takes practice and guidance for youth to: be able to keep notes, know the appropriate behaviour and expectations, and think about meaningful questions to ask. I also work with the individual(s) before the meeting to send them some sample questions we will be asking (brainstormed as a group beforehand), length of time, and clarity on our expectations and goals of the task.

Meeting and having a conversation outside with a community member. There are so many people who are in our own communities that have a connection to place. Connecting with an indigenous elder, a local gardener, city planners, scientist, photographer … Create a journal page that represents what they have shared and what they have shown you in that outdoor space.

What is their relationship with the outdoor space?

What key information did they share?

Extension: after keeping notes the students can circle all the comments that:

Are important to your community.

Could help you answer a geo-inquiry question (a community question or issue).

What could we do to lead to positive change.

What could you learn by answering these questions or issues?

Temperature and Weather:

The temperature and weather can be collected through-out the year. An excellent example of this can be seen here: https://www.pyrosketchology.com/nature-journaling-before-fire

The weather can also be added in as a note on the side of journal page every time students sketch outside to have a running document.

Water:

Water can be tested for the pH, temperature, clarity, among other things. A daily journal of these facts can be added into squares for each day.

Sound Map

Close your eyes and listen. Rarely are we in a completely silent space.

Tell students about deer ears, which are shaped to pick up the slightest noise from the surrounding area. Have students cup their hands so that if you were to pour water into their hands they would be able to hold some - and then have them put their cupped hands behind their ears to listen to naturally occurring noises.

In a bottom corner they draw the map’s key. Each new sound heard will be represented with a symbol they come up with and recorded in the key. Ask students to also draw an X and their name on the place they are on the map. As each new sound is heard, the symbol is recorded on the map at where it was heard relative to the X on the map.

Now focus on one sound and translate that sound into an image. Draw that sound, listen for a new sound, draw again. The very act of translating a sound into an image, forces students to pay attention and describes a part of the environment.

How did you feel about the human sounds you heard? Why?

Are their sounds you cannot identify?

Patterns:

Patterns can be seen everywhere in nature. There are large patterns (such as the year), as well as small patterns (such as branches).

Sun Dial:

On a sunny day, give each pair of students a pointed stick. Ask the students to find a spot in the grass where they can push the pointed stick into the ground, so it stands upright. Tell them to mark where the shadow falls. Have the students return twenty minutes later, marking the tip of the shadow. Tell them to use the meter stick to form a line on the ground connecting the two marks.

Why does this line represent an east-west direction?

Ask the students how to determine the north-south line. (The north-south line will be perpendicular to the east-west line.)

Then ask the groups to draw a second line, crossing the first at a right angle. Verify their findings with a compass. Ask the students how they would use this activity if they were ever

lost.

How does the length of the object’s shadow change over the course of the day? Why?

After creating sundials, the students were able to make a sundial in their journals.

Food Webs and Food Chains:

Taking what students know about food webs and food chains, go outside and add in what they can find that represents key aspects.

What producers, consumer, or decomposers are evident in your area?

What food chains and food webs do you want to learn more about?

Scale- perceptions:

Smaller scales can inform our understanding of that object. Map-makers use defined scales—usually a large-scale map depicts a small geographic area in great detail while a small-scale map depicts a large geographic area in much less detail. Find one object that interests you. Draw it in the middle of a journal page at the scale that feels the most manageable. Now above and below your first sketch, use a larger scale and a smaller scale to view the same object.

How does this affect your perception of the object?

What does observing something from a new perspective make you learn more about it?

Close-Up Observations:

Students love getting a "window" to draw and focus on one spot. Cut a picture frame out of cardboard or thick paper. Place this on the ground (or have students look through) to focus on one small area. Have them focus on things they may not have noticed before.

What small things to you notice? Make sure to label the size (either estimation based on referent like the size of my thumb nail, or using a small ruler).

How small is it when it is born?

How far does it travel?

Tree Observations:

There are a variety of observations and data collect that can be made with trees. Choose a tree for the exploration. You may want to bring out some tree identification keys so the students can identify their tree. Students could record the following observations for each visit: date; estimate of the number of leaves or needles (this can be done by counting the leaves or needles on the lower branches, then count the number of branches, and multiply); the colour of the leaves; obvious changes since last visit. After collecting the base data for each visit, any series of activities can be drawn together around the specific tree. For instance, students might observe, sketch, identify and research…

Here are some ideas:

Ask the students to work together to write a paragraph about their tree. Their description should be so specific that a stranger could locate their exact tree with just this information.

Have them move around their tree to get different views.

Draw the general silhouette shape of the tree.

Look from the bottom of the trunk up to the top of the branches and draw what you see.

Locate any roots that might be visible at the tree’s base.

Do a tree bark rubbing (by hold a loose sheet of paper on the trunk and lightly rubbing a crayon or chalk along the sheet). How does the bark compare to the skin on their own hands? Is the bark rougher or smoother; warmer or colder; wetter or drier; darker or lighter than your skin?

Tell the students to look for and sketch any seeds, cones or flowers.

Listen to the sounds made by the tree. How can you draw the sounds in your journal?

Ask the students to look for small holes in the tree, or other places where animals, or other plants might be living.

What animals live in or use this tree?

What do you see on the tree?

Why does a tree need roots? (food and water transport, support).

If the tree is coniferous, ask the students to search for some sap or resin and describe its texture and scent. Tell them to rub a bit of the resin next to the bark rubbing in their journal. Why do you think the resin is sticky?

Draw the branching pattern of the tree.

How do the branches come out of the main trunk?

Have the students describe the colour and shape of the leaves or needles.

Sketch or trace a leaf. Describe the edge of the leaf.

Why does a tree need leaves? (Leaves photosynthesize, or produce food, with the help of sunlight, air and water.)

How do the leaves or needles come off the branch? Are they in opposite pairs; or alternating around the branch; or do they come off in a whorl, like a shirt collar?

Collect and sort leaf samples to determine the plants growing in the natural area. Classify leaf shapes and draw the details.

Insect Observations: Remember to talk about the importance of how to release and unharmed insects.

Idea from: https://resources4rethinking.ca/media/5%20Min-Fieldtrips.pdf 5 Minute Field Trips by GEOEC

Lay a white sheet below a small bush or shrub and have students rustle the bush so that anything clinging to the branches or leaves will fall out. Show how items like magnifying glasses can be used, and briefly model the observation skills you would like students to use.

Other idea for observing insects include:

Search for and investigate the creatures living in the mulch layer of the soil.

Search for and investigate galls on plants to see who lives where.

Investigate an insect’s behaviour by making observations of a single insect’s journey. Draw the insect looking closely or draw the line of where the ant moves (creating a squiggle across your page).

Plant Watch:

Sketching and journaling is a wonderful way to get to know the plants around you. As students focus on the details they will often see many details and find a deeper sense of that plant. Again, this is not an art task to draw the perfect flower, but rather a way for student to develop deep observation skills and notice. Students develop scientific skills while observing changes in plants and learning about biodiversity.

There are many observations that can be made while looking at plants. Some include:

How many petals?

Draw what the fragrance of the flowers would look like. What colour would it be?

Are the leaves alternating, or opposite on the stem?

Draw the plants life cycle.

Show its seed.

Students monitor the flowering and document the bloom times.

If the plant faces threats, such as pollution or loss of habitat, students can develop a recovery plan.

Observe and identify native flowers.

Monitor pollinator populations in natural area.

The sky’s the limit for ideas on how one student and one plant can relate.

Ethnobotany is the study of how plants have been used by various people and cultures around the world. Seek local examples of plants that were traditionally used for food, beverages, and medicinal remedies.

Tracks and Scat:

A great way to have students engage in the winter months is to draw the tracks that are found around them. Remember to show how the tracks are placed (as often it shows the type of movement of the animal).

Feeling:

Colours and memories can often add to the feeling of a space. Instead of trying to draw what you observe, try drawing capturing the feeling of a space.

What colours are there?

What textures can capture the mood?

Tracing:

Students love tracing. A leaf, rock or other treasures found on the ground can be observed with details in the tracing.

Six Directions:

Developed from Lynda Barry's book What It is: Do You Wish You Could Write?

Sit is space and notice what is up, down or below, in front, behind you and on both sides. Make 6 boxes on your page and document what you notice.

The Natural Cycle: Adapted from Coyote’s Guide

Prepare a series of cards (8.5 x 11 cardstock) with each of the 8 cardinal directions on it, and another set of cards for each layer of meaning that you want to introduce:

■ Directions

■ Times of day

■ Seasons

■ Stages of Life

■ Qualities of the 8 directions / energy levels

■ Learning cycle

Get students sitting in a circle and ask them to point in the 8 cardinal directions. Ask them what comes to mind when they think of each of those directions.

Place the cards for the 8 directions in front of students in the correct orientation.

Introduce as many new layers of meaning as you would like, for example “Here are the different stages of life (Infant, Toddler, Child, Adolescent, Young Adult, Adult, Elder...) and where would they fit in the circle?.” Discuss. This can be connected to Indigenous teachings through the integration of the Medicine Wheel teachings. The complexity of meaning for each direction will be differentiated depending on your group.

Six Room Poetry:

from Georgia Heard's book Awakening the Heart: Exploring Poetry in Elementary and Middle School.

VISUALIZE

envision, picture, see, imagine, evoke, fancy, dream up, conceptualize, think about, forecast, anticipate,

In this stage the students are creating compelling visuals and organizing data to deeper understand, and analyse data that was collected. It is a visual representation of data and information. In this phase, students show how they are fully immersed in a sense of their surroundings and have a deep connection and understanding. Nature journaling exercises often find different ways of seeing, thinking and organizing information, and this helps with the storytelling of this journey. The students may have started visualizing their information already as they engaged in the collect phase. The following are ideas on how to continue to organize and present that information.

Boxes:

Info-doodles:

Create a page of integration of words, images, numbers, and shapes for the purposes of learning and sharing what has been learned. Students use both words and sketches to communicate their ideas. Encourage them to include labels, arrows, diagrams, and anything else to make their thinking clear to another scientist.

Word Cloud:

Create a word cloud by making a collection, or cluster, of words depicted in different sizes (and you can play with different fonts).The bigger and bolder the word appears, the more important it is.

Concept- Map:

A concept map begins with a main idea, typically placed in a circle, and then has lines connecting the main idea to other ideas. This strategy helps students visualize relationships among different concepts. Reviewing their concept maps will give you a sense of students' understanding, how their ideas are connected, and any gaps or misconceptions they may have.

Frayer Model:

From: A Schema for Testing the Level of Concept Mastery by D. A. Frayer, W. C. Frederick, & H. G. Klausmeier.

The term being looked at is added into the middle of the page. Around the outside there are definition, characteristics, example, and non-examples.

Descriptive Observation:

Look through your journal and think about what observations you have made. Create a page in the journal that summarizes the story or journey you have been on.

What are some key things you think that can be helpful in a story page?

What other observations can you notice?

What data can you observe in this space, that can help you at the end of the geo-inquiry process to compare how you have impacted this space for the better?

Create a time line of your natural area:

When you step outside your door each day to interact in the natural world, consider who may have walked this land before you and who will walk this land after you are gone?

Think about how the land supports your health and well-being, and that of your family, community and all non-human entities within the web of life?

Think-Pair-Share with Writing:

Students write their own thoughts in the first box during the "think" period. After the "pair-share" discussion with a partner (or partners), they write down what their partner said in the second box. Finally, they record in the third box how the conversation has changed or confirmed their initial ideas.

Information Cards:

Information cards are cards that can be kept in a pocket made in the journal to remember key information and facts. One side has the image to help you remember, and the other side has some information.

4 (see), 3 (feel), 2 (hear), 1 (smell):

4-3-2-1 -- The world is out there, ready to explore. Try “4, 3, 2, 1” as a way to tune into your observations; taking time to engage your sense in the natural world. Outside find 4 things you can see, 3 things you can feel, 2 things you can hear, and 1 thing you can smell.

What do you notice?

This task can also be adding information and ideas for what we have shared in the journal earlier about a space.

CREATE: design, originate, invent, initiate, devise, frame, shape, form, forge, establish, bring about, foster, sow the seeds of, inspire, enkindle

At this phase the journal becomes a way to convey a story that has formed from the data and information. It represents how to show the answers you have found about your geo-inquiry.